(And Why Most Actors Never Learn to Use Them)

If there is one skill — one — that has the power to transform your acting more than anything else, it’s Verb Work. Not “figuring out your character,” not planning out emotions, not line readings, and certainly not backstory. And yes, I know some acting teachers are big on backstory. While I agree it can be incredibly useful for writers, in my experience it does one very unhelpful thing for actors: it gets you in your head and out of the moment.

Verb work does the opposite. In fact, verbs give you everything actors are usually chasing — instantly and viscerally. They generate truthful dramatic behavior and release real emotion in you, in your scene partner, and most importantly in the audience. They give you something to do, which keeps you from getting swallowed by nerves or anxiety. They build neural pathways that allow you to trust and ride your instincts. And they create character for you, without having to patch together externals. Verb work is the beating heart of the Liechty Acting Technique and one of the main reasons AIAC actors book as consistently as they do.

How I learned to “Verb”

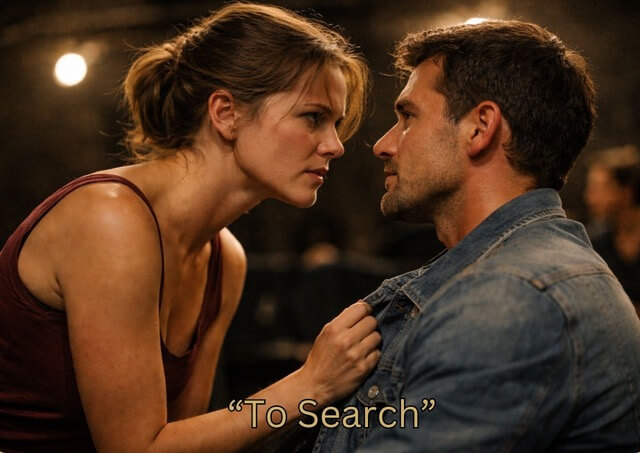

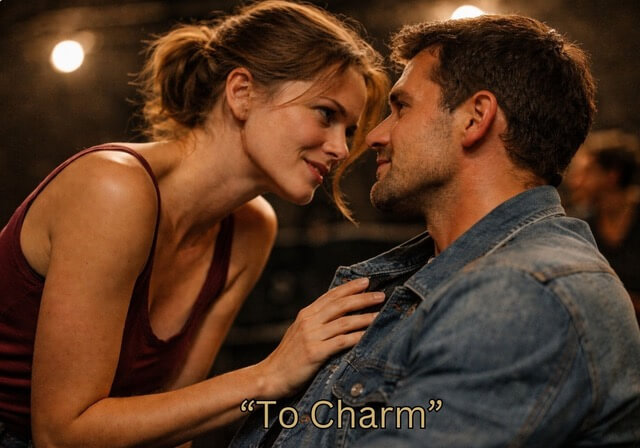

I first encountered verb work in a college acting class, before I was accepted into The Theatre School at DePaul University and transferred there. We were handed a verb list several pages long — a list I still have, which eventually became the foundation for my current verb list of over 2,000 verbs. The instructor mentioned something about Stanislavski, told us to “play verbs,” and then moved on. We were instructed to “evade” our partner, or “charm” them, or “threaten” them, but no one really explained how to do that or why it worked. Even later at DePaul, verbs were discussed often, but the instruction consistently stopped just short of what actors actually need: how to make the verb show up clearly in behavior.

Years later, I began studying my own audition playbacks. I wanted to see what was really happening in my work and how I could improve it. I thought I was using verbs, but when I watched the tapes back, they weren’t readable. They weren’t landing. So I started experimenting. I practiced playing verbs, taped myself, reviewed the footage, and tried again. At first, nothing changed. Then one day — boom. I could see the verb clear as day. What surprised me most was how subtle and grounded the acting became. It wasn’t showy or forced. It was real. I remember watching the playbacks and actually feeling moved by my own work because it felt honest.

That was when the real breakthrough happened. I realized verbs aren’t intellectual concepts — they’re labels for behavior. When you choose a verb and play it clearly, with real intent, it reads as visceral human behavior. The camera understands it. Your partner understands it. The audience understands it. I also noticed my energy stopped circulating inside my head and began moving outward — into my partner, into the camera. A forward flow. I started calling it Forward Motion, and I recognized it immediately from real life. It’s the same energy we experience when we want something, encounter an obstacle, and keep pressing forward anyway.

That, I realized, is acting. Using a behavior — a verb — to push against an obstacle in order to get what you want inside an imaginary circumstance. Once I understood that, everything opened up. I saw how profoundly powerful verb work was, and I realized that with enough practice, I could access it on command.

That discovery became the foundation of the Liechty Acting Technique. I had found a tangible, repeatable, teachable way to act — and to teach others how to act. And it was, without question, thrilling.

Verbs In Action

If the story above hasn’t already convinced you to explore verb work, here are a few more reasons verbs are one of the most powerful tools an actor can train.

Why Verbs Matter More Than “Emotions”

Actors who chase emotions almost always run into the same problems. They start faking or pushing. They squeeze for feeling, think too hard, act out the words, panic when the emotion doesn’t arrive on cue, and disconnect from their partner in the process. The truth is simple: emotions are side effects. They are not the engine.

Verbs are the engine. When your verbs are precise and clear, emotions show up naturally, appropriately, honestly, and often unpredictably. Verbs are the action, and the action drives the emotion. As I tell my students over and over again: acting is not about feeling something. Acting is about doing something. That “doing” is your verb. Just like in life, when the behavior is real, the emotion follows.

Verbs Create the Dramatic Pathway of the Scene

Every scene has a built-in dramatic structure. You want something. There’s an obstacle. You do something to overcome it. Your partner responds. You adjust. The behavior escalates. The scene resolves — or explodes. Verbs are those “somethings” you do. They are the fuel of the dramatic pathway.

Think of verbs as the behavioral engine underneath everything the audience sees. When you’re forcing emotion or trying to play an idea of a character, or intellectualizing, the scene falls flat. But with well-picked and played verbs you’re in the moment, embodied, specific, and active. The scene starts to breathe. You light up. Your partner lights up. The audience wakes up. Casting sees truth. Everything becomes electric.

Verbs Are Physical, Not Mental

This is where many actors misunderstand verb work. They treat verbs as ideas instead of actions. But verbs are physical. They live in the body. They shape the breath, shift the ribs, change the voice, activate the senses, and push energy into your partner. When you play a verb well, you feel it. Your body knows exactly what to do. Your instincts fire. Your listening deepens.

This is why one of the most repeated phrases in my class is, “Do the verbs BIG at home.” You must condition your nervous system to feel the verb. Then — and only then — can you scale it down for subtle, camera-ready acting without losing the behavior underneath it.

Verb Work Is Intimate (And Why That’s a Good Thing)

Actors are often surprised by how vulnerable verb work feels at first. Playing a verb is intimate because it reveals your need, exposes your desire, drops your armor, and forces you to reach toward your partner. It invites response. It risks rejection. It requires honesty.

When actors first begin working this way, they often feel exposed, shaky, overwhelmed, or like they’re doing something wrong. But as they lean into that vulnerability, something extraordinary happens. Their acting becomes simple. Pure. Unforced. Magnetic. Alive. This doesn’t come from “character.” It comes from truthful behavior — generated by verbs.

Verbs and Listening: The Twin Pillars of Truthful Acting

Verb work increases your ability to listen to your partner — not pretending to listen, not waiting for your next line, not “being in character.” Real, somatic, moment-to-moment listening. In class, I use the phrase “checking with your partner.” By checking, I mean reading your partner’s current state, letting that effect you truthfully and using that information to instinctively adjust your verb playing to get what you want from this current version of them in this moment.

Most actors never do this. They set a choice, lock into it, and flatten the scene with predetermined behavior. But truthful behavior is always relational. It’s dynamic. It breathes. It changes you. Behavior cannot exist without listening, and listening cannot exist without behavior.

Why Subtle Verb Work Still Requires Big Practice at Home

I often tell actors, “You must play verbs uncomfortably big before you can play them subtly.” If the behavior isn’t alive in your body, subtle acting becomes invisible. Actors who skip the conditioning phase end up doing flat acting instead of subtle acting. Flat acting is dead acting. Subtle acting is alive behavior with micro physicalization — and the difference is massive.

This is why AIAC actors train big so they can deliver small, powerful, and deeply readable work on camera.

Verbs Are the Fastest Way to Level Up Your Auditions

Casting directors watch hundreds of tapes, and they all light up when one thing happens: the actor takes action. Most audition tapes look the same — flat, conceptual, emotional without behavior, polite, safe, disconnected. But when you play verbs, your tape jumps off the screen. You’re affecting your partner. You’re embodying intention. You’re taking risks. You’re alive. You’re unpredictable in a truthful way. You’re connected to the dramatic structure.

This is why I tell students, “If your verbs are clear, you are already ahead of 99% of actors auditioning.”

How to Practice Verbs (The AIAC Way)

Here is the training process we use at AIAC. With your scene first, play your verbs big — uncomfortably big. Like a 11 or 12 on a scale of 10. It should feel ridiculous. Good. That’s how you wake up the body. Notice what each verb does to your ribs, breath, voice, posture, shoulders, impulses, gestures, and energy direction. Then go down the scale and play the verbs at a 7 or 8, then a 5 or 6, etc. Until you’re playing them at a 1 or 2. Play them tiny— tiny but clear. This becomes your on-camera version.

From there, work against real obstacles. Push against something that resists you. You can use a chair. (We call this “Chair Work”.) Play your verbs to the chair, letting your energy go into it, feeling the physical obstacle pushing back against you. Notice the tangible conflict you feel. Then play the scene again sans chair. Watch how much more grounded, dynamic, and truthful the work becomes. This is the work. This is the craft.

The Real Reason Verbs Are So Transformative

Playing verbs requires courage, vulnerability, presence, generosity, listening, imagination, emotional muscle, body awareness, breath discipline, and nervous system regulation. In other words, playing verbs makes you a better actor — and a better human. Your empathy expands. Your emotional capacity expands. Your ability to stay embodied expands. Your courage expands. Your truth expands. Your artistry expands.

This is why AIAC actors evolve so quickly. Verb work isn’t about “acting.” It’s about being a fully alive human inside imaginary circumstances.

Closing Thoughts: Verbs Are Your North Star

If you strip everything else away — the training, the voice work, the personalization work, the script analysis — this is what remains: acting is action. Action is verbs. Verbs are behavior. Behavior is truth.

Verbs anchor you. They free you. They challenge you. They reveal you. They sharpen you. They liberate your acting from self-consciousness. And if you learn nothing else but how to play verbs truthfully, consistently, fully, and courageously, you will become an extraordinary actor.